Sam Contis / MATRIX 266

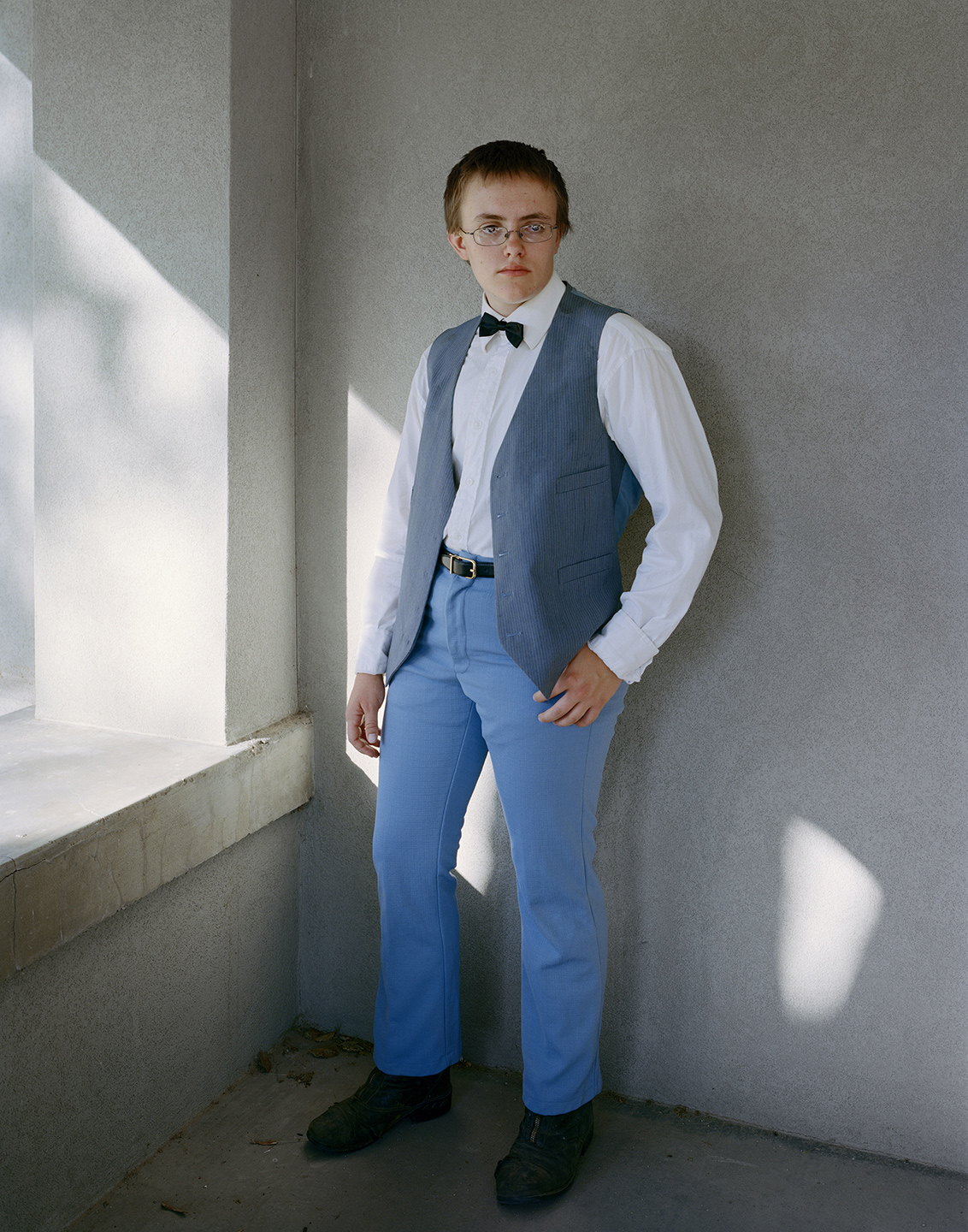

In her most recent body of work, Sam Contis uses photography and archival research to explore the relationship of bodies to landscape and the shifting nature of gender identity and expression.

The photographs in this exhibition were made at Deep Springs College, one of the country’s last all-male institutions of higher learning, which is located in a remote desert valley on the California– Nevada border. Contis’s images capture the strange beauty of the high desert in macro- and microscopic views. The resonance of earth and body and the sensual echoes of human and animal give her works an Ovidian sense of imminent metamorphoses. Contributing to this sensation of superabundant possibility is the mythic potency of the American West.

America’s fascination with the desert West was sparked by the landscape images that photographers such as Carleton Watkins and Timothy O’Sullivan brought back from their survey expeditions. O’Sullivan’s explorations of the American West were done as part of US government-funded expeditions between 1867 and 1874, and his images capture both the beauty of the land and the changes being wrought to the area by miners and settlers, railroads and new cities. Contis references the grand vistas of these photographic pioneers while offering a more intimate view of this fragile and multi-faceted landscape.

Deep Springs College was founded in 1917 by the engineer, industrialist, and educational visionary Lucien Lucius Nunn. Inspired in part by the pedagogical theories of John Dewey, Nunn sought to create a school combining Socratic learning, self-governance, and manual labor, as well as isolation from society. Although practical education was to some degree the underlying premise of the curriculum, Deep Springs is profoundly idiosyncratic, placing its inhabitants in a world very different from the reality they will likely enter upon graduation.

For generations, the West has symbolized an ideal of freedom and self-determination even as it has defined a rough, often violent ideal of masculine identity. Deep Springs can seem, in many ways, to be an embodiment of these ideals. For example, in addition to their academic studies, the twenty or so students operate a ranch of about two hundred head of cattle, and raise animals to be slaughtered for food. The American cowboy of bygone days spent weeks in the saddle, sleeping rough under the stars, and sharing camaraderie and companionship with an all-male team in relative isolation from the larger society. Even now, this ritual is replicated annually at Deep Springs when two of the students are selected to drive the herd on horseback to the summit of the White Mountains, where they spend the summer together watching the cattle graze.

While the “cowboy” is essential to the Western myth, and a central figure in American masculine ideals, Contis’s photographs allude to another side of both the historical and present reality; that is, an experience of gender that is more nuanced and open to ambiguity. In the early days of the American West, when women were few and far between, it was not uncommon for men to take on traditionally female roles. Similarly, at Deep Springs, gender identity has always been open to fluid expression. And coursing through Contis’s photographs is a powerful countercurrent of softness, gentleness, and fertility.

In addition to creating singular images, Contis is concerned with the syntactic relationships among works in a series. She arranges her works in the gallery in ways that draw out formal echoes and poetic resonances, especially those that undermine a predominantly masculine gender narrative. She suggests analogies between male bodies and the landscape, inverting the conventional trope of earth as female form. Images of young men nurturing plants or reclining in the nude balance pictures of dusty struggles in the corral or a blood-spattered cloth. Against the backdrop of ageless mountain ranges, the historically constructed categories of gender seem to melt away like a desert mirage.

–Lawrence Rinder, Director and Chief Curator, BAMPFA

In this presentation Contis has also included a number of photographs borrowed from the Deep Springs archive, including images made by some of the first students at the college a hundred years ago.